"The board game rewarded something in play that hurt people in reality," Anspach thought, according to Pilon's account. But with an oil crisis developing and consumer suffering on the rise, the game's message seemed less fun. Later, in Berkeley in the early 1970s, he played with his wife and sons.

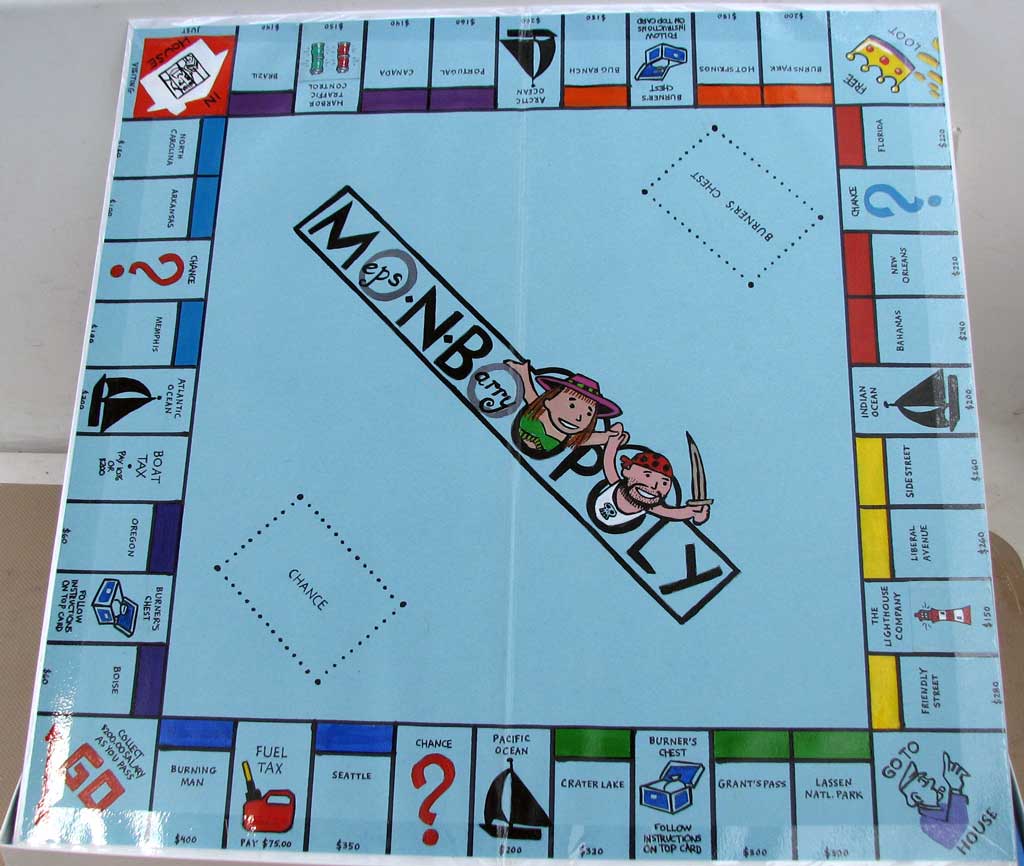

Anspach was a German Jew who had immigrated to New York with his family in 1938, according to Mary Pilon's 2015 history of Monopoly, " The Monopolists."Īnspach played Monopoly in Czechoslovakia as a child, Pilon wrote. The Anti-MonopolistĪnti-Monopoly was the creation of Ralph Anspach, who in 1973 was teaching economics at San Francisco State University. He sought answers from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered community reporting project. "I thought I knew this town well, so I wondered where that could be." "We thought, 'God dang, they destroyed all those games in Mankato?'" Trieschman said. The retired firefighter and lifelong Mankato resident wanted to know the location of the burial site, and who manufactured the games. Reader Mike Trieschman learned of the Anti-Monopoly graveyard in a recent PBS documentary about Monopoly's history. The saga remains a prominent chapter in the history of Monopoly, the most popular modern board game. Parker Brothers, then a division of Golden Valley-based General Mills, obtained a federal court order to have the game buried. Then, much like in Monopoly, the ownership class quashed the competition. Manufactured in Mankato, the game Anti-Monopoly found success in the mid-1970s amid America's rampant inflation and institutional distrust.

Somewhere beneath southern Minnesota lie the remnants of about 40,000 board games once created and sold as an antiestablishment alternative to mega-selling Monopoly.

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)